Avant-garde as Software

Excerpt:

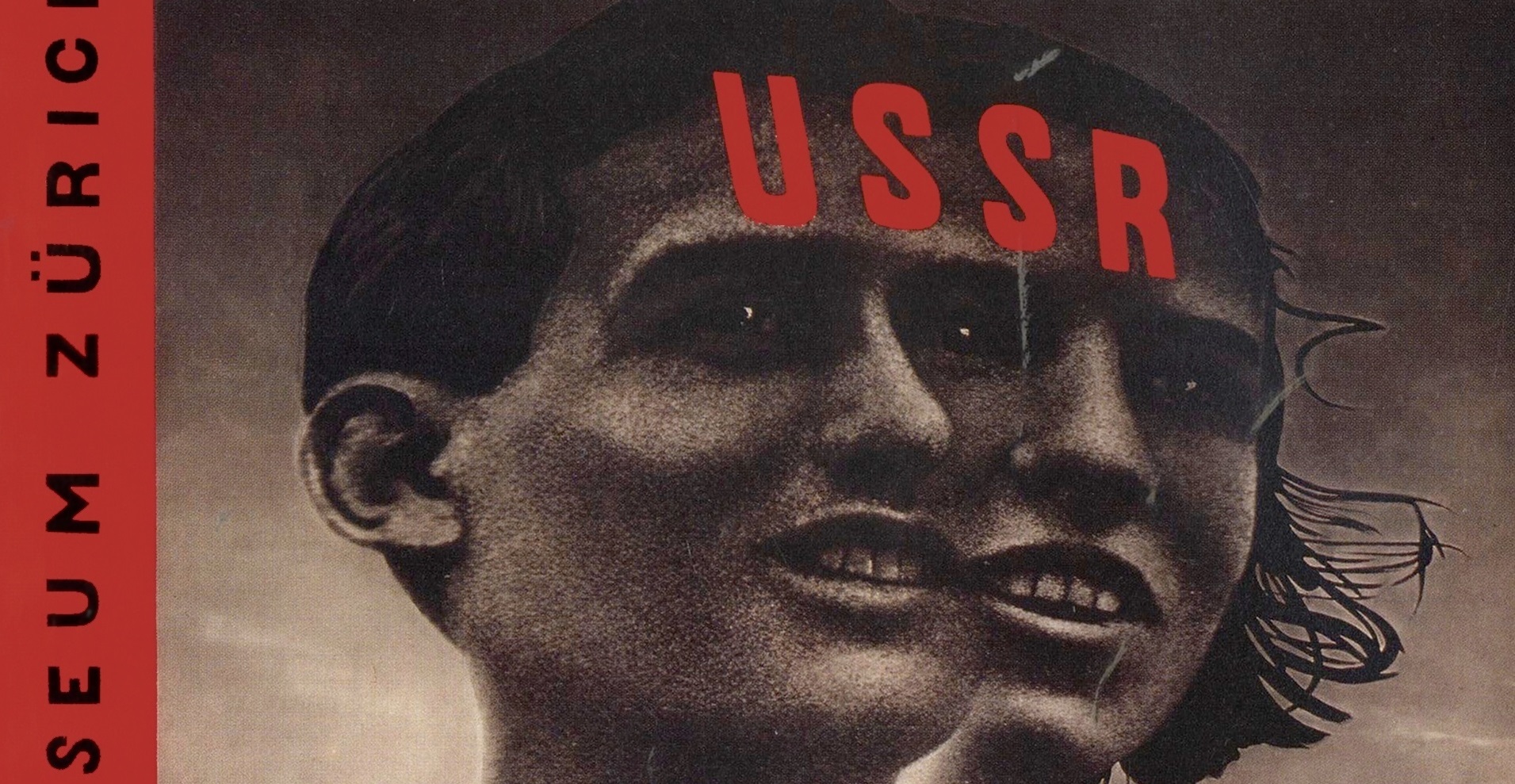

During the 1920s a number of books with the word “new” in their title were published by European artists, designers, architects and photographers: The New Typography (Jan Tschichold ), New Vision (Laszlo Moholy-Nagy ), Towards a New Architecture (Le Courbusier ). Although nobody, as far as I know, published something called New Cinema, all the manifests written during this decade by French, German and Russian filmmakers in essence constitute such a book: a call for a new language of film, whether it was to be montage, “Cinéma pur” (also known as “absolute film”), or “photogénie.” Similarly, although not declared in a book, a true visual revolution also took place in graphic design thus “making it new” as well (Aleksander Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, etc.)

In the 1990s the word “new” re-appeared once again. But now it was paired not with particular media such as photography, print, and film but with media in general. The result was the term “new media.” This term was used as a short cut for new cultural forms which depend on digital computers for distribution: CD-ROMs and DVD-ROMs, Web sites, computer games, hypertext and hypermedia applications. But beyond its descriptive meaning, the term also carried with it some of the same promise which animated the just mentioned books and manifests from the 1920s – that of the radical cultural innovation. If new media is indeed the new cultural avant-garde, how can we understand it in relation to earlier avant-garde movements? Using already noted parallels as a starting point, this article will look at new media in relation to the avant-garde of the 1920s. I will mostly focus on the most radical sites of the avant-garde activities of the 1920s: Russia and Germany.