Navigable Space

Excerpt:

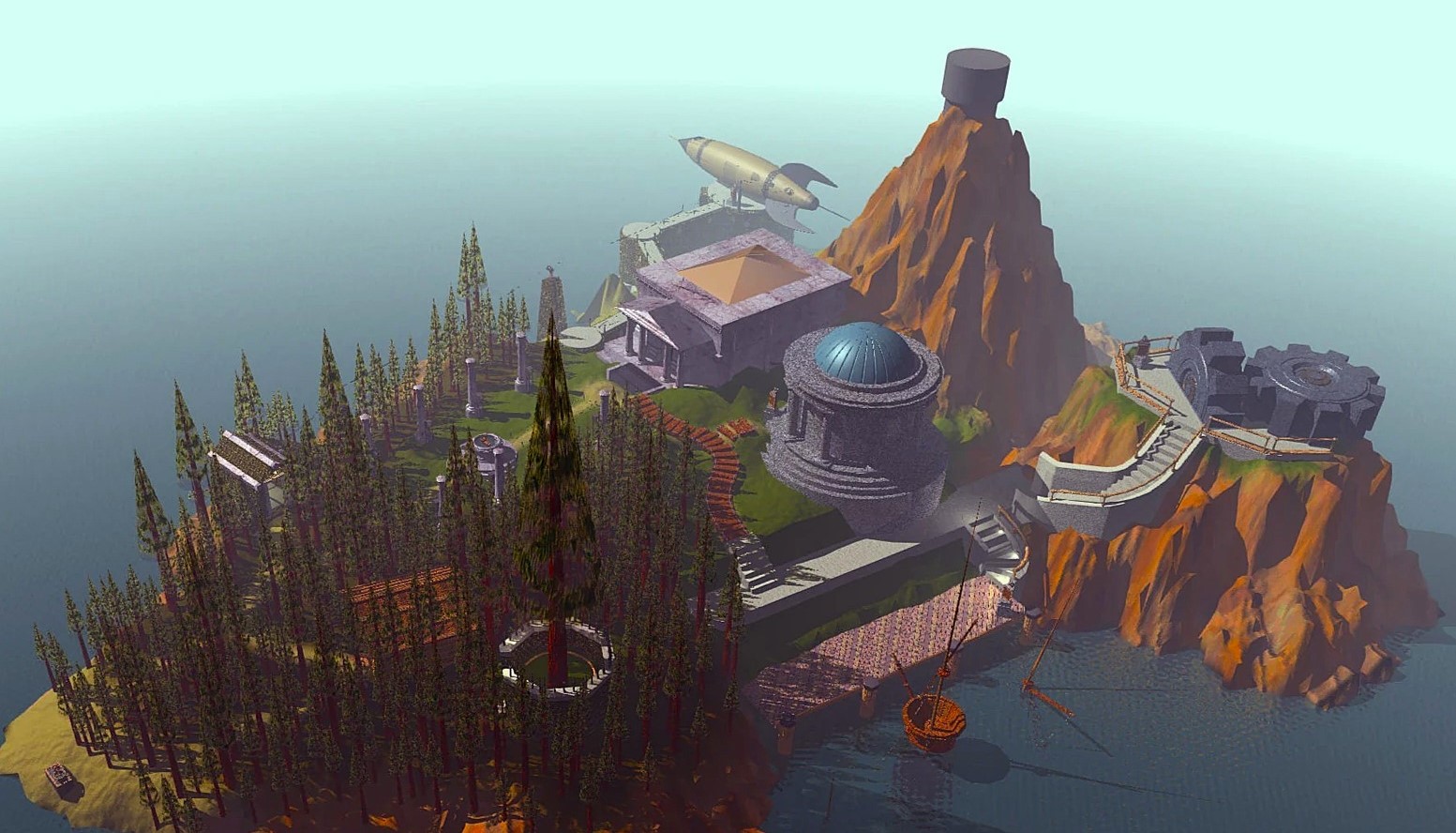

Looking at the first decade of new media — the 1990s — one can point at a number of objects which exemplify new media’s potential to give rise to genuinely original and historically unprecedented aesthetic forms. Among them, two stand out. Both are computer games. Both were published in the same year, 1993. Each became a phenomenon whose popularity has extended beyond the hard core gaming community, spilling into sequels, books, TV, films, fashion and design. Together, they defined the new field and its limits. These games are Doom (id Software, 1993) and Myst (Cyan, 1993).

In a number of ways, Doom and Myst are completely different. Doom is fast paced; Myst is slow. In Doom the player runs through the corridors trying to complete each level as soon as possible, and then moves to the next one. In Myst, the player is moving through the world literally one step at a time, unraveling the narrative along the way. Doom is populated with numerous demons lurking around every corner, waiting to attack; Myst is completely empty. The world of Doom follows the convention of computer games: it consists of a few dozen levels. Although Myst also contains four separate worlds, each is more like a self-contained universe than a traditional computer game level. While the usual levels are quite similar to each other in structure and the look, the worlds of Myst are distinctly different.

Another difference lies in the aesthetics of navigation. In Doom’s world, defined by rectangular volumes, the player is moving in straight lines, abruptly turning at right angles to enter a new corridor. In Myst, the navigation is more free-form. The player, or more precisely, the visitor, is slowly exploring the environment: she may look around for a while, go in circles, return to the same place over and over, as though performing an elaborate dance.

Finally, the two objects exemplify two different types of cultural economy. With Doom, id software pioneered the new economy which the critic of computer games J.C. Herz summarizes as follows: "It was an idea whose time has come. Release a free, stripped-down version through shareware channels, the Internet, and online services. Follow with a spruced-up, registered retail version of the software." 15 million copies of the original Doom game were downloaded around the world. By releasing detailed descriptions of game files formats and a game editor, id software also encouraged the players to expand the game, creating new levels. Thus, hacking and adding to the game became its essential part, with new levels widely available on the Internet for anybody to download. Here was a new cultural economy which transcended the usual relationship between producers and consumers or between “strategies” and “tactics” (de Certeau): the producers define the basic structure of an object, and release few examples and the tools to allow the consumers to build their own versions, shared with other consumers. In contrast, the creators of Myst followed an older model of cultural economy. Thus, Myst is more similar to a traditional artwork than to a piece of software: something to behold and admire, rather than to take apart and modify. To use the terms of the software industry, it is is a closed, or proprietary system, something which only the original creators can modify or add to.

Despite all these differences in cosmogony, gameplay, and the underlying economic model, the two games are similar in one key respect. Both are spatial journeys. The navigation though 3-D space is an essential, if not the key component, of the gameplay. Doom and Myst present the user with a space to be traversed, to be mapped out by moving through it. Both begin by dropping the player somewhere in this space. Before reaching the end of the game narrative, the player must visit most of it, uncovering its geometry and topology, learning it logic and its secrets. In Doom and Myst — and in a great many other computer games — narrative and time itself are equated with the movement through 3-D space, the progression through rooms, levels, or words. In contrast to modern literature, theater, and cinema which are built around the psychological tensions between the characters and the movement in psychological space, these computer games return us to the ancient forms of narrative where the plot is driven by the spatial movement of the main hero, traveling through distant lands to save the princess, to find the treasure, to defeat the Dragon, and so on. As J.C. Herz writes about the experience of playing a classical text-based adventure game Zork, "you gradually unlocked a world in which the story took place, and the receeding edge of this world carried you through to the story's conclusion." Stripping away the representation of inner life, psychology and other modernist nineteenth century inventions, these are the narratives in the original Ancient Greek sense, for, as Michel de Certau reminds us, "In Greek, narration is called 'diagesis': it establishes an itinerary (it 'guides) and it passes through (it 'transgresses").