Watching the World

The article first appeared in Aperture magazine, No, 214 Spring 2014.

Excerpt:

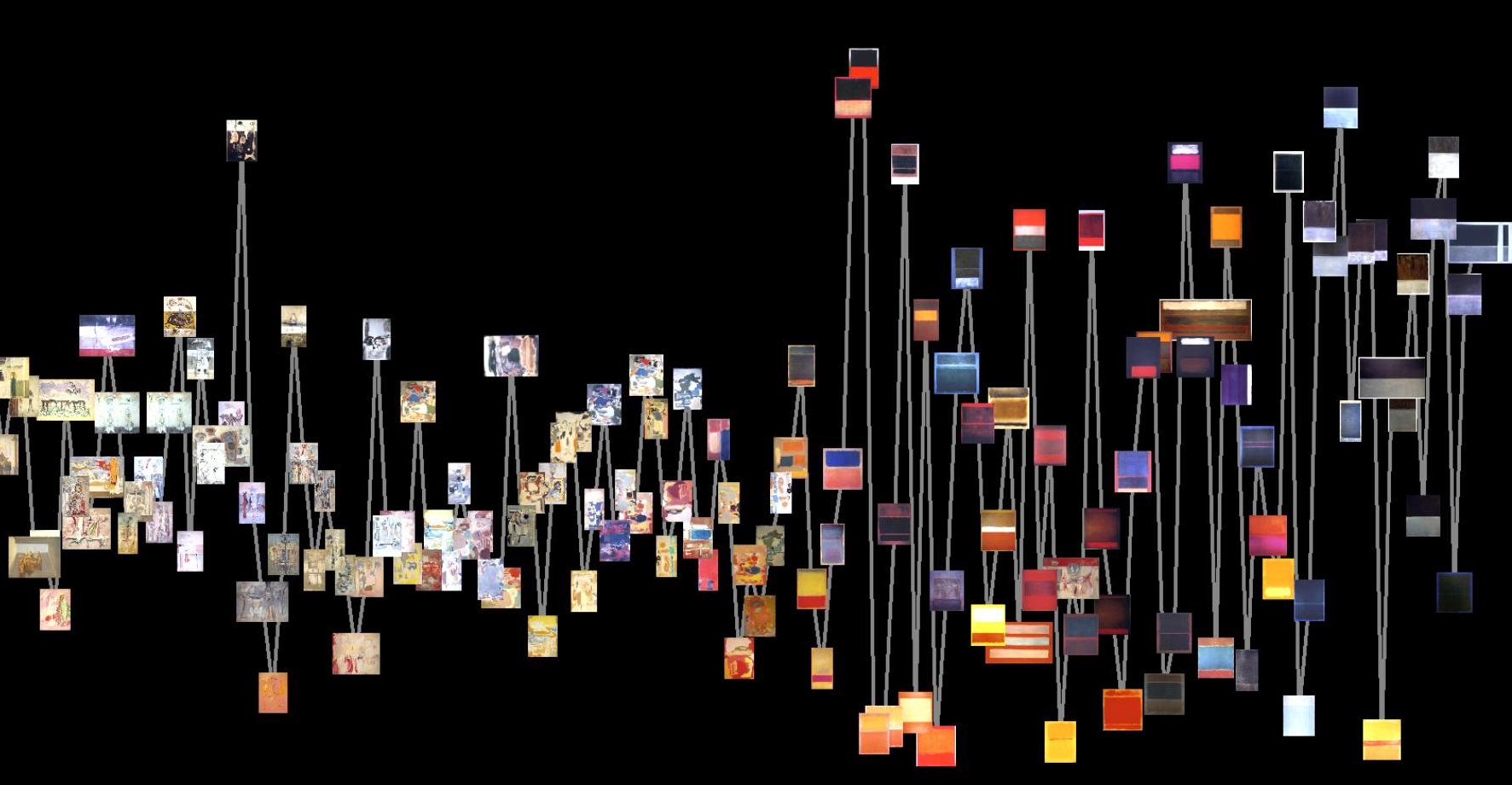

Last summer the Museum of Modern Art in New York asked the Software Studies Initiative, a program I started in 2007, to explore how visualization could be used as a research tool, for possible methods of presenting their photography collection in a novel way. We received access to approximately twenty thousand digitized photographs, which we then combined, using our software, into a single high-resolution image. This allowed us to view all the images at once, scrolling from those dating from the dawn of the medium to the present, spanning countries, genres, techniques, and photographers’ diverse sensibilities. Practically every iconic photograph was included—images I had seen reproduced repeatedly. My ability to easily zoom in on each image and study its details, or zoom out to see it in its totality, was almost a religious experience.

Looking at twenty thousand photographs simultaneously might sound amazing, since even the largest museum gallery couldn’t possibly include that many works. And yet, MoMA’s collection, by twenty-first century standards, is meager compared with the massive reservoirs of photographs available on media-sharing sites such as Instagram, Flickr, and 500px. (Instagram alone already contains more than sixteen billion photographs, while Facebook users upload more than three hundred fifty million images every day.) The rise of “social photography,” pioneered by Flickr in 2005, has opened fascinating new possibilities for cultural research. The photo-universe created by hundreds of millions of people might be considered a mega-documentary, without a script or director, but this documentary’s scale requires computational tools—databases, search engines, visualization—in order to be “watched.”

Mining the constituent parts of this “documentary” can teach us about vernacular photography and habits that govern digital-image making. When people photograph one another, do they privilege particular framing styles, à la a professional photographer? Do tourists visiting New York photograph the same subjects; are their choices culturally determined? And when they do photograph the same subject (for example, plants on the High Line Park on Manhattan’s West Side), do they use the same techniques?

To begin answering these questions, we can use computers to analyze the visual attributes and content of millions of photographs and their accompanying descriptions, tags, geographical coordinates, and upload dates and times, and then interpret the results.